MERCHANT-BASED MONEY LAUNDERING PART 3: THE MEDIUM IS THE METHOD

/Editor's Note: This article originally appeared on the Association of Certified Financial Crime Specialists website on September 21, 2017.

The previous editions of this series on merchant-based explored the many manifestations of the dark side of the terminal, including suspicious transactions merchants may see that could be tied to fraud groups and the risks tied to both closed loop and open loop prepaid cards.

To read the first story, covering “phantom shipments,” please click here. To read the second story on “prepaid gift card smurfing,” please click here.

Merchants can be involved with phantom shipments to move value across borders and cash can be anonymously loaded on prepaid gift cards through smurfing operations and used at US merchants to make sales revenue appear legitimate.

The rules and actions of the payment sector have direct implications on bank anti-money laundering programs.

How? Because while banks are technically not liable for the illicit actions of their customers’ customers – the customers of a merchant or payment processor – the bank is on the hook for properly inquiring about the risk of that customer base and compliance procedures, if any, of the merchants.

At issue is that if a merchant or fraudulent site is later tied to a particular financial institution, and that bank never took the time to engage in the proper level of due diligence, creating a defend-able risk score and adequately tuning the transaction monitoring system, in the eyes of regulators, the bank could have a weak financial crime compliance program.

This article will focus on transaction laundering (TL), in its various forms, which I would argue is a subset of the broader problem of merchant-based money laundering (MBML). While it may appear that MBML is another form of trade-based money laundering (TBML), they are actually quite different for one reason.

To sum up a key mantra we will explain more on later, keep this in mind: the medium is the method.

In the 1960s, Marshall McLuhan coined the iconic phrase, “The medium is the message,” as he became the oracle of the electric age. But what did he really mean, when he said the medium is the message?

Fundamentally, McLuhan was pointing to the fact that how information is delivered to us through different mediums influence how we interpret the message itself and how it portrays social structures and our understanding of the world.

For instance, let’s take a lot at the tectonic shift in the human experience of conveying information when the world went from hand-writing and copying information to the printing press – which allowed for more wide-scale distribution of knowledge and ideas.

To be sure, the invention of the printing press was arguably one of the most important moments in human history and drastically influenced the development of the modern world.

Before the printing press, text would have to be copied manually by hand, which was inefficient, costly, and led to low rates of literacy.

Once printing was mechanized, it allowed for high rates of literacy and the rapid exchange of ideas. In that same vein, we think of money or value transfer as a medium which followed a similar evolution of the acoustic, written, mass production, and electric ages – going from a physical, spatially-limited form of value to a digital, internationally-fluid funding mechanism.

That idea is important to remember because one of the earliest adopters of new monetary technologies is the criminal element.

But let’s look for a moment at how different mediums affect our sensibilities to better understand the challenges to crafting criminal defenses against all the many ways money can move.

Just like television and radio has a completely different effect on our senses, laundering value through cash and merchant terminals leaves a completely different signature, something banks, regulators and investigators have to realize to balance the challenge of stopping criminal groups without creating customers friction and delays.

This is one of many fundamental struggles in the fight against money laundering, because many of the models we use today treat all forms of value transfer the same in terms of fighting financial crime and creating compliance programs, only looking at a few basic data points.

Additionally, regulators don’t want to stifle innovation, but they need to find ways to impose sensible regulations to keep pace with new mediums of money or value transfer.

Source: The Independent

The payments ecosystem as a new medium

As we said, however, in order to create current, relevant and agile ways to counter increasingly aggressive and creative organized criminal and terror groups, you need to understand how the United States structures its payments and settlements systems, and the panoply of players in the game, including banks, retailers, merchants, money services businesses, prepaid card providers, third-party payment processors and others.

The payment ecosystem in the US is complex and has a whole host of entities involved.

When a consumer makes a card purchase at a store or online, the payment flows through the payments ecosystem with the end goal of funding the merchant’s account, assuming the transaction is approved.

A consumer-initiated card purchase is commonly referred to as a “pull-payment” because the funds are pulled from the consumer’s account and deposited into the merchant’s account[1]. The three main steps of the payments process initiated by a consumer card purchase are:

- Authorization

- Funding

- Settlement

All of the above steps in the payments ecosystem involve various entities including, but not limited to the customer, merchant, gateway, processor, association and issuer.

[1] http://www.knowyourpayments.com/transaction-basics/

Source: Know Your Payments

What is transaction laundering?

Now that you have a better sense of the players in the payment chain and who does what, now we need to look at how criminals and fraudsters are trying to game the system.

Transaction laundering happens when a known merchant processes transactions for an undisclosed business.

This clandestine business is usually selling illegal products or services, and leverages the known merchant’s card processing accounts either through collusion or coercion – or simply because the merchant’s card processing systems are not tuned to be sensitive to financial crime and fraud red flags.

As a point of context, while banks, money services businesses and other entities considered a “financial institution” are subject to anti-fraud and anti-money laundering (AML) requirements, merchants typically are not, along with most third-party payment processors.

However, under current AML structures, some banks have foisted AML duties onto payment processors as a duty to continue to hold the account in the face of rampant de-risking in the financial sector, while third-party processors themselves may have to shoulder some counter-financial crime duties depending on how a prepaid payment chain is structured tied to recently-enacted rules.

Now, back to some of the red flags that can be employed by miscreant merchants.

The unknown businesses selling illegal products and services can disguise themselves in a number of ways, but here are some common examples described in a video by Dan Frechtling from G2 Web Services[1]:

- Cannabis sales intermingled with toy transactions

- Pirated movies appearing as software

- Prohibited injections posing as vitamin sales

Similar to red flags in the AML context, a guiding principle to determine if something is suspicious is if the transaction details don’t make sense for what the merchant should be doing or where they should be doing it.

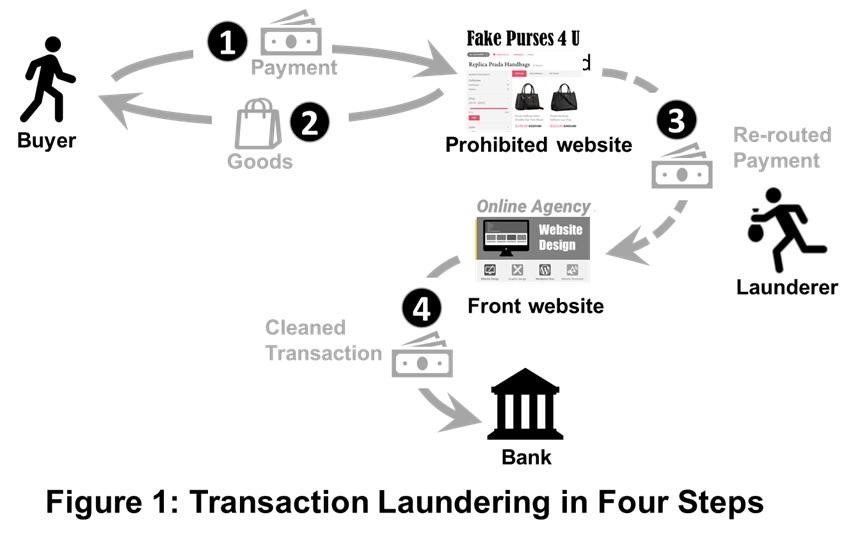

There are a number of challenges identifying transaction laundering, but one fundamental difficulty is that the complex payments ecosystem allow illicit transactions to enter through a variety of channels including, but not limited to: carts, gateways and virtual terminals. The below diagram illustrates a common example of transaction laundering:

[1] https://www.g2webservices.com/acquiring/g2-portfolio-protection/transaction-laundering/

Source: Transaction laundering in four steps https://www.g2webservices.com

But transaction laundering doesn’t end there.

The payments made for illicit products or services through the known merchant on behalf of the unknown business will be withdrawn from the known merchant’s bank account at some point in the future.

This is the touchpoint with the traditional banking world because the known merchant must have an account with a bank which receives the settled payments.

The ill-gotten gains can exit the merchant’s bank account through a number of methods, but the bank wouldn’t know of any suspicious activity and potential transaction laundering scenarios, unless the merchant acquirer informed the bank of the situation.

This obviously creates the need for a great deal of collaboration and information sharing between the merchant acquirer and the banks which hold the merchant accounts.

Who's responsible for transaction laundering?

Transaction laundering or credit card laundering is seen as a variation of money laundering by the U.S. Treasury’s Financial Crimes Enforcement Network (FinCEN) subject to suspicious activity reporting (SAR) requirements.

Transaction laundering violates several Federal Trade Commission, Telemarketing Sales, federal crime laws and some states have their own laws to address this problem. But that begs the question of which institution is supposed to file SARs?

Here is the answer, according to payment industry experts:

“Yet except for certain Money Services Businesses (“MSBs”), non-bank Third-Party Organizations such as ISOs/MSPs, Payment Facilitators/Payment Service Providers, data processors and network providers (collectively “TPOs”) generally are not subject to BSA requirements [highlighting mine]. Thus, it is the acquiring bank’s responsibility to (1) ensure that a TPO’s incident reporting and management program contains clearly documented processes and accountability for identifying, reporting, investigating, and escalating incidents of credit card laundering and other suspicious activity; and (2) monitor TPO compliance and processing information on an ongoing basis to ensure compliance with the acquirer’s SAR obligations.[1]”

As stated above, the answer is the acquiring bank.

This seems oddly familiar because this situation sounds a lot like correspondent banking. In correspondent banking, the correspondent bank provides services to the respondent bank’s customers or the “customer’s customers.”

Essentially, the correspondent bank is relying on the strength of the respondent bank’s AML program, but ultimately the correspondent bank is held accountable for the payments processed by regulators in their local jurisdiction.

But the U.S. correspondent bank – the operation could also be, say, a New York branch of a foreign bank – processing the overarching transactions will be held accountable for properly risk-ranking the correspondent’s AML program and divining the overall risk score, something several foreign banks have been penalized for recently.

Similarly, the acquiring bank is relying on the payment processors to have adequate controls in place to detect transactions derived from illegal activity.

As regulatory actions focus more on payment processors, they could also face a round of de-risking practices, similar to what is occurring now in the correspondent banking space, by banks in the payments ecosystem.

Hence, it’s clearly in the best interest for payment processors to vigorously monitor their merchants’ activity and inform the acquiring bank of any instances of suspicious activity – lest they find they are tied to an illicit organized criminal group and become radioactive to global banks.

Beware cloaked illicit online gambling portals

Beyond shady and unscrupulous online business looking to dupe consumers and merchants, actors in the payment supply chain must also worry about illicit online gambling sites hiding their activities behind front company sites seeming to selling an array of innocuous items to not bring attention to themselves – in one recent case hiding behind a site selling household items.

On June 22, 2017, Reuters published an exclusive story which described an elaborate transaction laundering scheme used to circumvent local online gambling laws. Here is a short excerpt from the article below:

“The scheme found by Reuters involved websites which accepted payments for household items from a reporter but did not deliver any products. Instead, staff who answered helpdesk numbers on the sites said the outlets did not sell the product advertised, but that they were used to help process gambling payments, mostly for Americans.[2]”

This story was important because it was one of the first times a major publication detailed a transaction laundering scheme with real investigative reporting.

As these stories keep coming out from major publications and are linked to more heinous crimes, then it could help shine the spotlight on the risks of e-commerce and the connections to the criminal underworld.

Another challenge that the story indirectly highlighted was that even if merchant acquirers and payment processors could identify transaction laundering, they may not be able to identity the actual people behind the scheme due to the minimal customer due diligence being done in the industry.

Rather than a race to the top for compliance best practices in the traditional banking space, the payments industry has almost become a race to the bottom to offer no hassles and low fee structures in a highly competitive marketplace.

This can be illustrated by some entities in the payments ecosystem, as Dan Frechtling put it, offering “frictionless onboarding.”

Frictionless onboarding is not necessarily a bad thing in itself, but if a minuscule amount of customer information is required to open a merchant account and the information is not verified, then it becomes a problem.

Acquirers and payment service providers that wish to implement frictionless boarding without compromising their review policies may offer conditional approval followed by more stringent scrutiny in a post-boarding “containment” area.

This issue hits on a perennial debate in the compliance community: the potentially negligible value of an extensive customer review and risk assessment process versus defining risk by the transactions the customer actually engages, including going out of expected boundaries, or dealing with countries and entities historically considered high risk.

At the same time, the current momentum to more quickly create relationships that lead to new business creates a new quandary: How can you prevent the same bad actors from opening new fictitious websites and merchant accounts, if you don’t always know who’s behind the scheme?

Don't die from a tie dye high

The risks of illicit groups working behind seemingly legitimate sites was brought into stark relief when investigators uncovered that a psychedelic t-shirt site, appropriately enough, was in actuality selling a tightly-controlled mind-altering drug

Lysergic acid diethylamide (LSD) was created by Albert Hofmann in Switzerland in 1938 from ergotamine, a chemical found in the fungus ergot. Dr. Hoffman accidently discovered the psychedelic effects of LSD in 1943.

The drug was experimented with for psychiatric reasons and the Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) even tested subjects to determine what type of mind control and wartime applications it may have.

In the 1960s, the counterculture movement popularized its mind-altering power and it was subsequently prohibited in both its use and distribution. Currently, LSD is listed as a Schedule I drug by the United States Controlled Substances Act, sitting alongside heroin, cocaine and, more controversially, marijuana.

LSD has been steeped in controversy where some leaders of the counterculture such as Timothy Leary touted its life-changing power and skeptics highlighting its dangers and links to accidental deaths caused by a profound state of altered consciousness.

For example, a student from Northern Illinois University was reported to have died as a result of LSD use when he fall out of a window[3].

Clearly, LSD is a very powerful drug, but unscrupulous merchants are still willing to sell it over the internet by disguising the real purpose of their websites.

Just imagine that if one was so inclined, you could find a website selling LSD, a schedule I drug, and order it with the click of a button and a credit card and have it delivered right to your door. Makes you wonder what else goes through the mail.

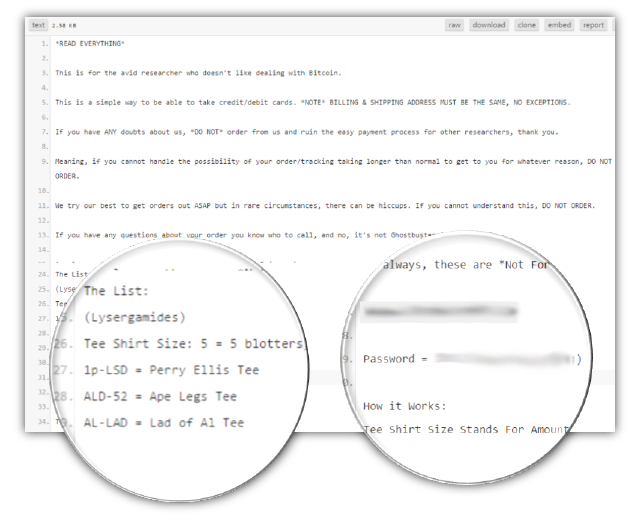

The below screenshot shows a real website appearing to sell tie dye t-shirts, but it was actually a front for a business selling LSD.

[1] https://www.g2webservices.com/blog/11865/acquirer-third-party-sar-obligations-transaction-laundering/

[2] https://www.reuters.com/article/us-gambling-usa-dummies-exclusive/exclusive-fake-online-stores-reveal-gamblers-shadow-banking-system-idUSKBN19D137

[3] https://www.inquisitr.com/2559752/lsd-becoming-popular-again-while-still-dangerous/

Source: G2 Web Services

The website itself has a number of red flags where the t-shirts are only offered in bulk and sizes are described in odd ways.

As well, the website had a checkout cart where if the credit card option was selected, it will send the visitor an email and redirect them to a separate website with a specific url link. This separate website was specifically designed to take credit card payments. One of the most interesting parts of this scheme was revealed below in a statement by the website operator:

“This is for the avid researcher who doesn’t like dealing with Bitcoin[1].”

[1] Source: https://www.g2webservices.com/blog/14723/real-life-launderers-tripping-transaction-laundering/

Source: G2 Web Services

This is actually quite a profound statement because it reveals the experience of the website operator conducting online drug deals was primarily with Bitcoin.

In other words, if a purchaser was so inclined to buy drugs online they could access the darknet via Tor and use Bitcoin to conduct their transactions almost completely anonymously as the only link to the illicit purchase would be the shipping address.

For online drug dealers to accept credit card payments, it shows they are serving a less technically savvy and larger segment of the drug market.

Anyone can make online purchases and the problem will only grow as people tell their friends about reliable drug dealing websites. Buyers don’t get the anonymity that the darknet and bitcoin offers, but it doesn’t seem to be slowing down the market.

Also, for the cautious and low value purchaser, they could load cash onto a prepaid card almost completely anonymously and would only be potentially linked to the illicit purchase based on the address provided.

But the United States in recent months have been targeting darknet drug bazaars and the virtual currency exchanges they are using, the key link to the real world and formal international financial system, in one case taking over a site undercover, watching and detailing the users and their online and fiscal exploits.

Drug dealer accepts credit card payments

One of the most brazen abuses of a merchant processing terminal was perpetrated by a local drug dealer in the United Kingdom.

The Police of Gloucestershire raided the home of Mark Slender on August 19, 2016 and seized cash, cocaine, cannabis, digital scales, and a chip’n’pin reader to take credit card payments[1]. The Police from Gloucestershire were shocked because they never saw a drug dealer take credit cards as a payment for drugs.

Slender even issued his customers receipts with the message, “Cheers, Gup.”

The Express article didn’t explain how Slender obtained access to a mobile chip’n’pin reader, but he could have been the one to open a merchant processing account on his own. This highlights one important point about the payment processing industry which is simply that there is no easy way to know, if merchants are selling illegal products or services through merchant processing terminals.

While most people buying illegal products would probably prefer some level of anonymity such as using cash in person or bitcoin on the darknet, some people may not even care or are so desperate to buy drugs that they use a credit card in the absence of cash.

Keep in mind that all many individuals need to process credit card transactions is an attachment to their smart phones and a bank account.

The publication reported that Slender was subject to a longer prison sentence due to previous drug dealing convictions. This raises an interesting point about the due diligence process for opening a merchant processing account and if a criminal background check would factor into the calculation of the fraud and money laundering risk profiles.

This is not to say that anyone with a criminal background should be prevented from opening a merchant account and processing credit cards, but they could pose additional risks to the institution.

Prohibiting new customers with criminal backgrounds may not be the answer at all, and could encourage more criminality, as such a practice, endorsed broadly, would push many suspicious actions underground, losing key intelligence federal investigators can use to take down larger criminal groups.

Ultimately, the customer with a criminal background poses additional fraud and money laundering risks, but they could be trying to rebuild their life and prohibiting them to open an account could prevent the reintegration into society as a whole and thus lead them back to the criminal life they may have been trying to escape.

Corporations are becoming more socially aware and active so this could be a situation where the institution absorbs the additional compliance costs of serving higher-risk customers for the greater good as opposed to simply de-risking whole categories of customers.

Don't wait for central registries and information sharing

While companies, retailers, processors, merchants and others try to juggle risk and find guys on an individual basis, countries as a whole must realize that larger organized crime groups and savvy fraudsters work internationally.

So the only way to stop them is forging stronger cross-border relationships with other firms and law enforcement because, currently, most countries don’t have central registries that detail high-risk or potentially criminal entities, currently the purview of third-party AML risk and list providers.

As well, while many large countries like the United States, United Kingdom and Europe have created county-wide financial intelligence units to store bank reports of potentially suspicious activity – and have attempted to better link these FIUs together – formatting, data privacy and resource constraints can conspire to limit their overall effectiveness.

Are the lack of central registries and information sharing between countries are a serious problem in the fight against money laundering and terrorist financing? Of course.

However, the problem with this argument is that it lessens the responsibility for each country, the country’s regulators and organizations operating within its jurisdiction to push the boundaries of what’s possible in the fight against financial crime.

There is a tremendous amount of external data sources that can be incorporated into AML programs to enhance detection capabilities including negative news, beneficial ownership and other open source data.

The advent of artificial intelligence, machine learning, and big data also open a whole host of new surveillance and analytic capabilities.

As with other forms of fraud, transaction laundering is more quickly exposed when firms use all their organizational eyes and ears. This includes sales representatives, underwriters, customer support staff and account monitors.

For example, G2 Web Services has observed adept organizations bring these professionals together to compare notes weekly or monthly, similar to the growing trend of convergence in the financial institution context where AML, fraud and cyber teams connect, cooperate and collaborate to better uncover illicit funds flowing through the bank and risks against the institution itself.

In the merchant-laundering arena, these notes may reveal conclusions about the same suspect business that were insignificant when singular but convincing when combined. In the event transaction laundering has occurred, cross-functional post mortems to look back for clues help banks avoid repeating mistakes.

[1] http://www.express.co.uk/news/uk/712043/Drug-dealer-uses-chip-pin-machine-take-twelve-thousand-pounds-customer-payments

Source: Collaboration across functions to spot transaction laundering, via G2.

Clearly, the payments industry doesn’t face the same type of AML and terrorist financing challenges as traditional banks.

However, this should not exempt the entities in the payments ecosystem from taking more proactive steps to identify and report suspicious activity. One of the challenges for organizations that have AML risk, but not to the extent of banks is that it's a slippery slope, and the cost of maintaining a comprehensive AML program potentially outweighs the perceived risks.

AML lite: One the periphery

What’s really needed for entities on the periphery of financial services such as attorneys, accountants, real estate brokers, merchant acquirers, payment processors, and FinTech firms is the idea of an AML lite program.

The traditional AML programs that have evolved in banks over the years tend to be top heavy, hierarchal, and slow to adapt to new trends.

While there will be significant challenges to come up with standards and solutions that smaller entities can adopt, additional AML coverage is needed across more industries to increase the identification of suspicious activity to help law enforcement to better put the pieces of the puzzle together.

Regulators also play a key role here.

These influential bodies sit in a tough spot because if they impose stricter AML regulations on entities that can’t adapt fast enough, then they could cause serious economic harm and put companies out of business.

On the other hand, if these entities, which sit on theperiphery of financial services are not required to comply with any rules, then it's likely they won’t do anything.

One strategy for regulators to continue to take, is to impose small incremental regulations for targeted industries and let the regulated institutions react and allow businesses to innovate and create services and solutions to meet those new requirements.

A recent example of this strategy was the action taken by FinCEN which renewed the “existing Geographic Targeting Orders (GTO) that temporarily require U.S. title insurance companies to identify the natural persons behind shell companies used to pay “all cash” for high-end residential real estate in six major metropolitan areas.”[1]

British Columbia implemented its own form of a geographic targeted order for any foreigners buying real estate in the Greater Vancouver Regional District (GVRD)[2].

Foreigner purchasers are supposed to pay an additional property transfer tax of 15% which was implemented as an effort to cool real estate market prices and to keep housing more affordable for the regular people of British Columbia.[3]

While it appears that British Columbia’s primary objective of the additional property transfer tax was to cool real estate market prices, it also likely reduced, to a certain degree, the amount of illicit funds flowing into the Vancouver real estate market.

Conclusion: A delicate balancing act for all involved

The fight against money laundering and terrorist financing is a delicate policy balancing act for regulators.

The AML industry is still in its infancy to a certain degree, because U.S. “The Patriot Act” was only signed into law on October 26, 2001 by President George W. Bush in response to the horrific 9/11 terror attacks.

That attack on the U.S. also pushed stronger global AML and counter-financing of terror standards, emboldening bodies like the Paris-based Financial Action Task Force (FATF), which is now the international standard-bearer of country-wide compliance structures.

So it seems Marshall McLuhan was right when he talked about the “Global Village,” because the world is smaller today and we are all more interconnected.

The technological advances of cars, trains, and buses allowed people to move farther away from the city into the suburbs. The internet and e-commerce allow us to buy almost anything, even LSD, with the click of a button.

The global village or the shrinking of the world has contributed to the difficulty in thwarting terror attacks because of the speed and variety of travel options available today. The evolution of how “value” is transferred is similar to transportation in the sense that value can move faster and in a wide variety of mediums today.

The car and airplane fundamentally restructured economies, cultures, and our perceptions of reality. Have we and society in general undergone a similar and perhaps more subtle transformation from the mushrooming mediums of value transfer?

No doubt, the human race has been shaped by these new ways to move money, just as we currently look for even newer, faster and cheaper ways to transact regionally and internationally. Just look at the advances of Bitcoin and its underlying technology the Blockchain.

But in step with the greater ability to move money quickly, easily and even, in some cases, nigh anonymously, detecting real instances of money laundering and terrorist financing in a reliable and automated fashion has grown even more incredibly complex.

Our understanding of how value is transferred and what are the potential exploits and weaknesses of each medium also must evolve to arrive at a more sophisticated approach to combat financial crime.

In other words, the medium is the method, requiring regulators, the private sector and watchdog bodies to craft new methods to better foster compliance, investigative and cooperative standards, best practices and methodologies to counter the entire spectrum of financial crime.

Such moves could formally or voluntarily nudge the payments sector to follow suit, making it harder for sham sites, fraudulent operators and illicit online casinos to engage in transaction laundering by arming merchants, processors, acquirers and others in the payments supply chain with the tools and resources to counter an array of criminal groups while supporting global commerce.

[1] https://www.fincen.gov/news/news-releases/fincen-renews-real-estate-geographic-targeting-orders-identify-high-end-cash

[2] http://www2.gov.bc.ca/gov/content/taxes/property-taxes/property-transfer-tax/understand/additional-property-transfer-tax#gvrd

[3] https://www.theguardian.com/world/2016/aug/02/vancouver-real-estate-foreign-house-buyers-tax